Overview

Patellar luxation is graded from I to IV, with grade I being the least severe, and grade IV being the most severe. These grades are applied by veterinarians based on their orthopedic exam findings, and they describe how much time the patella is spending inside of the normal groove where it should be located.

Some dogs may show a limp (lameness) due to patellar luxation, while other dogs may not have any obvious limp or discomfort. Dogs with patellar luxation are at an increased risk of tearing their ACL (in the dog, this ligament is actually called the cranial cruciate ligament, or CrCL but it is the same structure as a human’s anterior cruciate ligament/ACL). If a dog was previously diagnosed with a patellar luxation but was not showing a limp, then suddenly develops a limp, a tear of the cranial cruciate ligament is one possible explanation and surgery is likely needed.

Reasons for patellar luxation

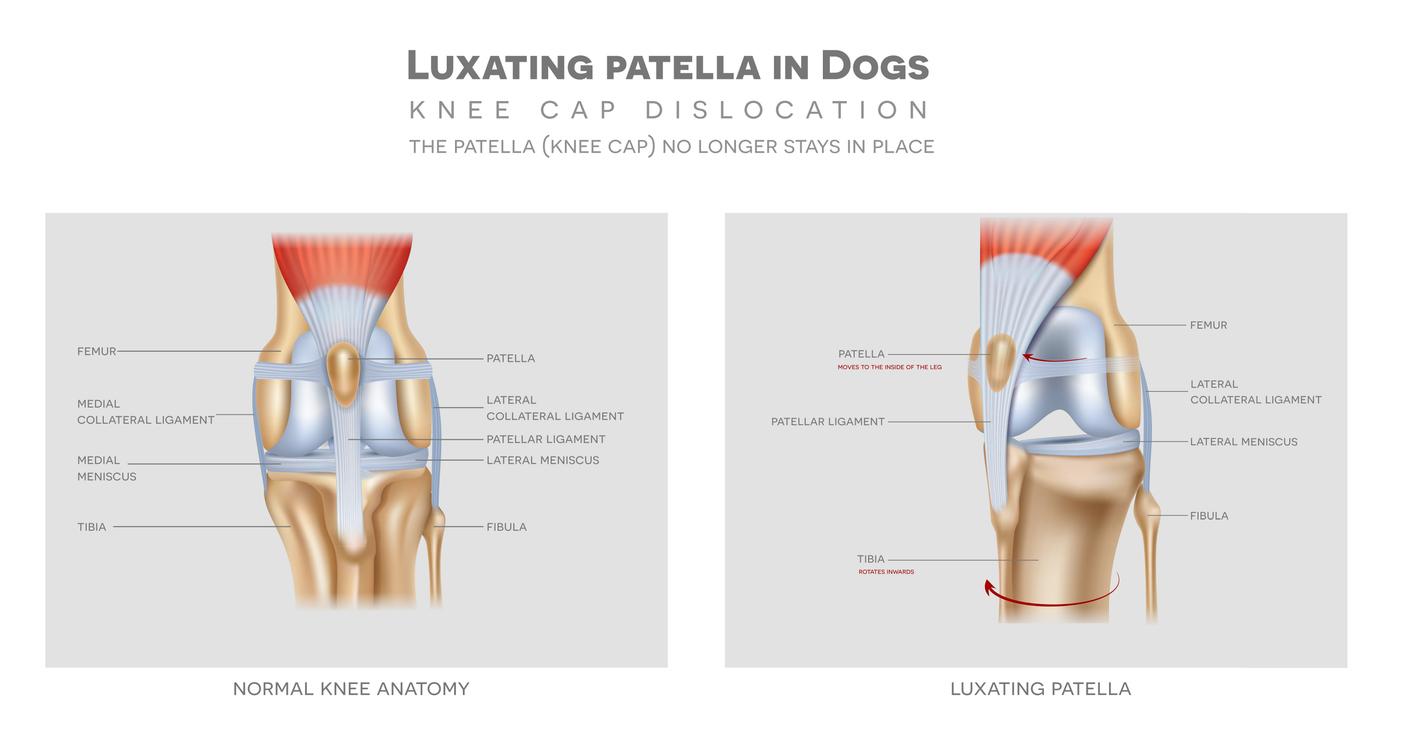

Often, dogs are born with patellar luxation but sometimes the grade/severity can worsen with time. The underlying developmental reasons that cause dogs to have patellar luxation can be due to one or a combination of these problems:

- A groove in the femur that is too shallow (trochlear groove).

- The bump on the front of the shin bone where the patellar ligament attaches can be in an abnormal position which pulls the kneecap toward that side.

- Twisting of the knee and shin bone (torsion), causing the kneecap to jump out of its normal groove toward the twisted side.

- The thigh bone can be curved or bowed and pull the kneecap out of the normal groove (this is more likely in large breed dogs, rather than small breed dogs).

- Tightening of the soft tissue (scar tissue) on the side of luxation, which pulls the kneecap to that side.

- Loosening/stretching of the soft tissue on the side away from the luxation, allowing the kneecap to move away.

Surgical options for correcting

Your veterinarian may advise surgery to correct patellar luxation if your dog is limping or painful. During surgery, the knee joint is examined to be certain there is no ACL/CrCL tear, and to determine which of the problems listed above is present. Based on the problems listed above, a surgical correction is made which may include:

- Trochleoplasty: Deepening of the groove in the femur to allow the kneecap to sit more deeply in its’ normal location and prevent it jumping/luxating out of the groove).

- Tibial tuberosity transposition: Moving the bump on the front of the tibia from its’ abnormal position to a more normal straight-line position on the shin bone to keep the kneecap in the center of the thigh bone and shin bone.

- Anti-rotational suture: to counteract the abnormal twisting of the knee and shin bone.

- Medial fascial release: Loosening the scarred tight tissue to prevent it from pulling the kneecap toward the abnormal position it was previously in.

- Lateral fascial imbrication: Tightening the loose tissue to help keep the kneecap in its’ correct location.